Alas, I am old. I can remember glimpsing the initial efforts of MTV on American TV screens and then, a little later, on the sets back in the UK. And I can recall the videos that dominated those early years of the nascent music channel too. There was a lot of Billy Ocean, way too much Def Leppard, and a whole series of dodgy Whitesnake videos (ask your dad).

But more than anything I remember MTV as essentially a promotional channel for Dire Straits. You couldn’t make it through even the briefest visit to the channel without Mark Knopfler and his band of middle-aged musos turning up on rotation and rocking out.

I hated it. Knopfler’s “bee-bop-a-lula baby what I say” lyrics. His stupid red headband. The obvious lack of cool. The unending guitar solos. It was everything a teenager was meant to hate. The opposite of what Frankie was saying and Morrissey was doing. So I hated it.

Time passed and I, to my total surprise, became old. And a strange thing happened. It occurred so slowly that the change was all but imperceptible. The odd foot tap. A twist of the dial every now and again. A brief smile when ‘Sultans of Swing’ started to play in a bar. The gradual addition of Knopfler’s songs to my Spotify playlist. A genuine love for ‘Sailing to Philadelphia’. I began to like Mark Knopfler.

It took 20 years but the very same songs I once winced at became acceptable, enjoyable even. If Knopfler toured anywhere within a 50 mile radius of me right now, I would go.

Something hated becomes loved over time. Call it the ‘Knopfler effect’. Ageing, lifestyle and the general passage of time mean that our tastes and behaviours evolve in relatively predictable ways. We encounter unavoidable demographic gateways along life’s winding road and they push us in different trajectories.

You pass 30 and suddenly find yourself magnetically attracted to the windows of real estate agents. You hit 40 and start gardening. You reach 50 and become enraged by the abject lack of quality in the music of today versus songs of yesteryear. And spend time bemoaning this fact to anyone you encounter.

There’s stuff you don’t think you will do when you get older. But you do. The Knopfler Effect is, to some degree, unavoidable. And it is suddenly at the heart of a huge debate currently engulfing television advertising and its ongoing centrality to marketers.

Up until now it would have been easy to assume that the relationship between TV broadcasters and Ebiquity, the marketing and media consulting firm, was extremely chummy. TV affiliates, like Thinkbox, quote Ebiquity research as the gold standard when making the case for TV advertising. Every time Ebiquity runs a big analysis comparing different advertising media, TV invariably comes out on top.

The reason Ebiquity is so attractive to TV marketers is that in the cacophony of bias and vested interests that is the modern world of media effectiveness, the company provides an expert and properly independent voice.

Ageing, lifestyle and the general passage of time mean that our tastes and behaviours evolve in relatively predictable ways.

Ebiquity runs the numbers and report the outcomes without any concern for any of the players in the media game. They are cold-hearted reporters of fact and when they do their gardening there is not a wall in sight. The name might suck – badly – but Ebiquity has come to stand for something that we rarely encounter these days in media: truth.

Its objectivity and influence mean that its new report, ‘TV At The Tipping Point’, has caused a significant amount of consternation in TV land. Ebiquity continues to cite TV advertising as the superior advertising medium for reach, ROI and long-term profitability. But its analysts are less certain that this superiority can be sustained beyond the next five years.

Specifically, Ebiquity thinks the current data from the UK suggests we are approaching a “tipping point” in which the gradual reduction in the reach of linear TV will have a demonstrable impact on its value and utilisation as an advertising medium.

TV’s uncertain future

This is not the ‘death of TV’, as predicted for the past decade. But it is an evidence-based analysis of tectonic changes in the current landscape of media planning. And it hinges on the existence or absence of the Knopfler Effect.

Let’s explore these complex points via a series of charts.

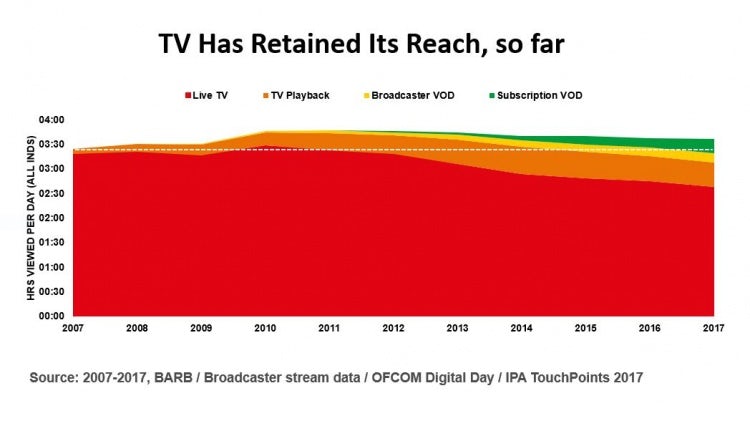

Despite significant changes in the media environment – specifically the emergence of subscription and ad-funded video-on-demand (VOD) options like Netflix and YouTube, respectively – TV’s reach and the time spent with the medium by the total audience have held up remarkably well thus far.

Marketers who tend to be single, urban and more digitally obsessed have looked at their own lack of TV viewing, extrapolated it to the general population, and concluded that linear TV viewing is already in terminal decline. The data from this country and elsewhere has plainly shown that to be untrue.

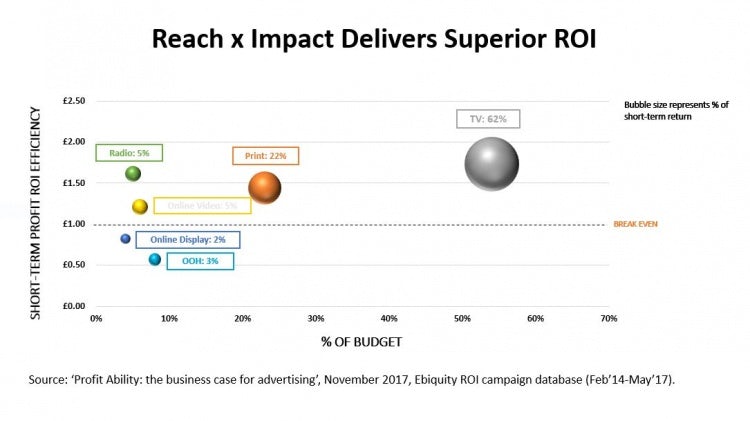

The combination of reaching so many people with great relative audience involvement and such an emotional medium has resulted in TV continuing to claim the crown as the most effective advertising medium. Clearly you have to possess the existing scale and distribution to justify TV’s big budget demands. But with those caveats acknowledged it is inarguable that TV ads are an important option for most big brands as they build their media mix.

Ebiquity has been at the forefront of the research to make this case. Its most famous assessment of different media concluded that even in the short term – and this data point will be important later – TV will generate returns superior to other media. Investing a quid in TV advertising will, all things being equal, likely generate a return that is 40% greater than any other alternative.

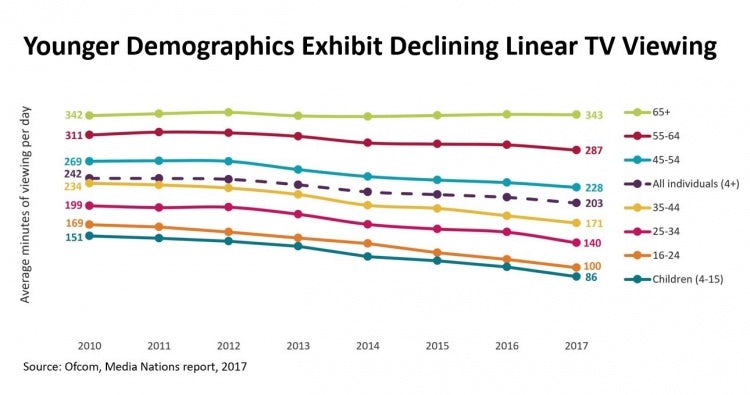

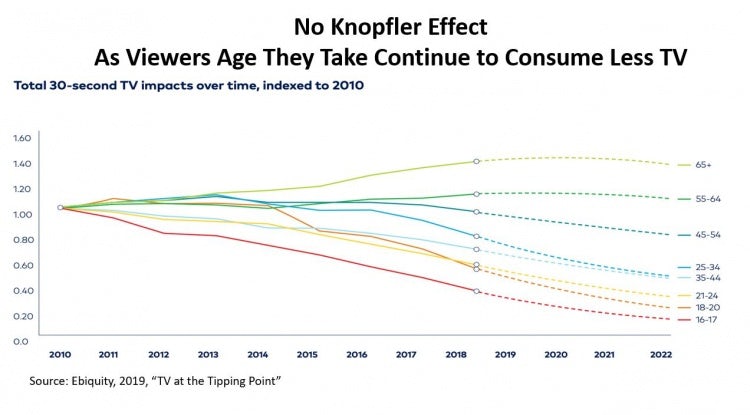

But all is not well in the world of TV. Older viewers (aged over 65) in the UK have continued to watch linear TV at the same significant levels as 10 years ago. But there is a direct correlation between audience age and reduced and reducing levels of linear TV watching.

Reduced, in the sense that younger people watch less TV. Reducing, in the sense that the younger the audience group, the steeper the decline appears to be occurring year to year.

There is a significant danger that younger demographic groups are not only watching less TV but continuing to watch less as time goes on. Obviously, it’s possible to extrapolate this data to a place where the 25-year-olds of today become the 65-year-olds of tomorrow, and ultimately predict a time when TV becomes an irrelevant medium for the 21st century.

This, of course, is the prevailing ‘death hypothesis’ so beloved by those who work in many corners of the digital world. But that might be an oversimplification – cue Dire Straits.

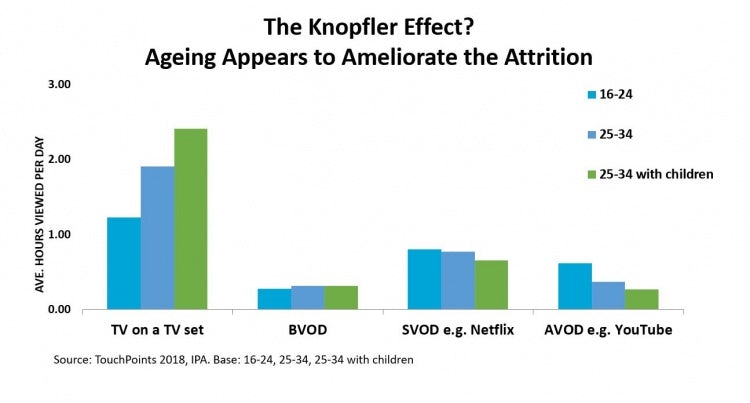

The counter argument to this death hypothesis is that young people eventually grow older. As they age they don’t necessarily continue to exhibit the same audience behaviours. The Knopfler Effect suggests that when and where they watch TV – and what they watch on it – might change in a manner that gradually replicates their older peers.

We become the boring, middle-aged fuckers we despised back in secondary school and our TV viewing eventually reflects this too. Younger demographics have always watched less TV simply because they have more fun and less reason to be at home.

They play sport. They go out in the evenings. They do a lot of fucking and even more looking around for people to fuck. Nobody ever got laid watching Bergerac (again, ask your Dad).

With the advent of ageing, kids, work pressures and the container-load of shit that middle age dumps onto most people from a great height, these once super-active 20-somethings eventually become exhausted 40-year-olds who flop onto their sofa at 7pm and reach for the remote.

They will probably not do it as much as their parents did in the 90s and noughties, but their TV watching should ramp up as the heady middle-aged cocktail of gentrification and exhaustion takes hold. That is certainly what the data in the chart above appears to show.

I say “appears” because this data from IPA’s Touchpoints database is comparative, not longitudinal. That’s critical because although it’s looks as if someone increases their TV viewing as they move through the two decades from late teenage years (the blue bar) to middle age (the green bar), that’s not what this data actually shows.

This is not the same person being measured across two decades; instead it’s different people of different ages being measured in the same year. It therefore assumes the Knopfler Effect, rather than empirically proving it exists.

The chart’s value hinges on the assumption that the 16-year-old of today turns into the 35-year-old of tomorrow. Twenty years from now, if we interview the teenagers that provided the data shown in that blue bar above, would we discover that their TV viewing now matches the current generation of 30-year-olds shown in the green bar? That’s what statisticians call a ‘big fucking question’.

According to Ebiquity there is growing evidence that if we were to stick around for two decades, or even half that time, and re-interview the teenagers of 2018 we would likely encounter an entirely different picture of TV viewing than the one we might expect from past generations.

Rather than assuming a Knopfler Effect in which younger viewers increase their TV viewing as they age, Ebiquity posits that these younger audience groups continue to reduce their TV viewing. Ebiquity suggests that the “inflection point” when the impact of this rapidly decreasing audience for TV begins to have a meaningful effect on the economics of TV advertising is approaching fast. It might be less than five years away.

As the 65+ group inevitably shuffle off to the great TV gameshow in the sky, as younger viewers with lower TV viewing habits replace them, and as their viewing continues to decline, the combination of these demographic changes begin to take their toll on TV advertising’s most precious advantage: reach.

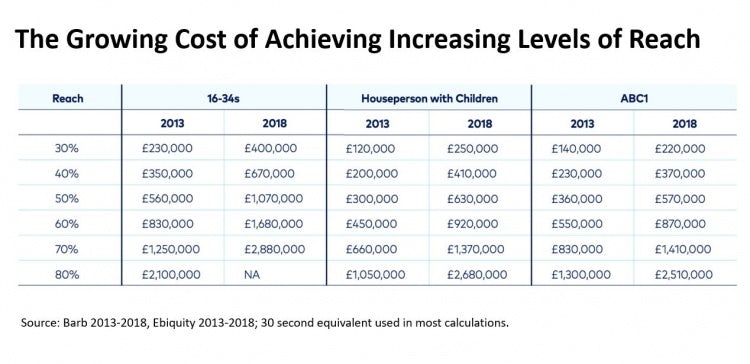

If these significant declines in reach are accurate – like all projections, they are open to debate – they will have a dramatic impact on the cost of effective TV in the near future. TV ads are sold using the individual spot price but they are valued and selected by advertisers on their ability to reach a certain proportion of the audience – a cost per thousand (CPM).

As the number of ads needed to reach that notional thousand viewers goes up so too will the relative cost of TV advertising – especially among the younger demographic groups so prized by advertisers.

The equivalent cost to reach a target audience with TV ads has already increased dramatically (see the table above). According to Ebiquity, that cost will continue to rise and by 2022 become prohibitive.

The cost to reach 16- to 34-year-olds will…